The importance of making an impact in the first few months of a new leadership role seems to be a well established truth. According to a study released in September 2005 by the US based leadership and training company Leadership IQ, 46 percent of newly hired employees will fail within 18 months, while only 19 percent will achieve unequivocal success. The study found that 26% of new hires fail because they can’t accept feedback, 23% fail because they’re unable to understand and manage emotions, 17% fail because they lack the necessary motivation to excel, 15% fail due to having the wrong temperament for the job, and only 11% fail because they lack the necessary technical skills.

The cost of this failure can be formidable. Organisations invest significantly to search, select and onboard new leaders, often using consultants to help them get the right candidate. The impact of a new hire not working out can be a considerable and costly disruption to the system. It can slow the organisations progress, demotivate staff and potentially damage the companies reputation. Equally, candidates want to succeed, make an impact and build success.

How then, can leaders make a positive impact in the first 90 days?

The answer to this question seems to be well documented with considerable content dedicated to the subject. In his book ‘The First 90 Days’ Professor Michael D. Watkins stresses the importance of this time and the need to stay focussed. To help with focus, Watkins suggests a number of orientating questions. The first is: ‘How will I create value?’ Beyond answering this question there seem to be a number of other tasks that need attention in order to make the first 90 days successful. High up on the list of priorities is connecting with others, forming relationships with colleagues, stakeholders and customers in order to build the guiding coalition necessary to make change happen. Other advice includes learning about the culture of the new system you’ve joined and understanding ‘the way things work around here.’ Knowing the social norms, conventions and organisational traditions will help you navigate your organisation’s political landscape. An appreciation of what is expected of you will be very important at an early stage. One tip that seems to be widely accepted is the delivery of ‘quick wins’ to secure confidence and credibility early.

Following the advice of Watkins and other experts is undoubtedly sensible, and taking a Systems Psychodynamic approach could also be helpful when working out not just what to do, but how to be. This way of thinking about organisations and the people within them means paying attention to how people feel, what is unsaid and unconscious, as well as how the system is organised to get ‘results’. In a 1997 paper Jean Hutton and colleagues from The Grubb Institute presented their idea the ‘organisation in the mind’. In this paper Hutton suggested that there are two key factors which every manager has to consider in taking up a new role. The first concerns the organisation that is intended; the stated aim and structure of the enterprise. The other is to do with what that is actually happening, this inevitably differs from the organisations intentions. It involves human beings who bring a diverse range of experiences, personal history and perspectives that influence how they see the world.

The Grubb Institute developed an organisational role analysis that enabled managers to stand back and explore their own experience of their organisation and roles through the concept of ‘organisation in the mind’. They discovered how this model helped managers become more aware of the realities of their situation and therefore enabled them to make choices and take action. This work requires leaders to tap into their own felt experience of a new role or organisation, feeling instinctively what is really going on.

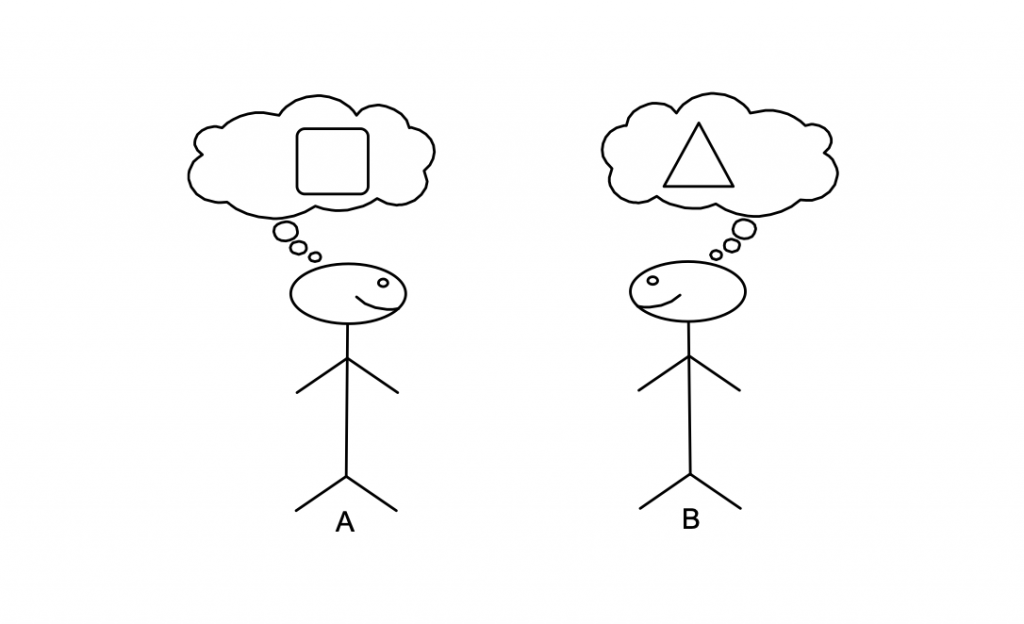

People from the same organisation can hold different pictures in the mind of the organisation they both work in. This can, of course, lead to people completely missing each other when trying to communicate. The basic point of reference about how things are organised is subjective. Awareness of this will help the new leader to consciously navigate their environment, rather than blindly stumble through it.

One area where this difference can be significant is in relation to peoples’ backgrounds. People of colour, women, people with differing sexual orientations, or different abilities will see their organisation through the lens of their life experience. A system that seems welcoming and supportive to one person could feel hostile and and persecutory to another. Person A sees a square and person B sees a triangle. These different interpretations of the organisation are more obvious when its stated intentions don’t match up with the lived experiences of people working in it. This can be particularly seen in relation to the organisations values and can be problematic when a gap between differing perceptions emerges.

The capacity to tune into your new environment may be as important as your analysis of the context. The distinction here is between an intellectual examination of the facts, and a felt experience of the new system. Far from a New Age practice, I first came across this method in Andy McNab’s 1993 account of an SAS patrol that had become compromised while operating behind enemy lines during the first Iraq war. In his book McNab describes the initial stages of infiltrating enemy territory as a process of ‘tuning in’. I recall him describing exiting the helicopter and finding a spot to be still, listen, observe and feel his new environment. This ability to connect with one’s environment in an embodied way was seen as a vital skill for special forces operatives, providing ‘felt’ intelligence that could only be recorded in the body.

What goes on ‘out there’ affects us ‘in here’

McNab’s method is akin to the practice of ‘Presencing’, a social technology for helping to create profound innovation and change. Pioneered by MIT Professor Otto Scharmer, the focus of this method is on sensing and actualising emerging future opportunities, both individually and collectively. Much like McNab’s tuning in process it involves attending to the felt experience of your body in order to focus on the system you’re operating in. What goes on ‘out there’ affects us ‘in here’. If this is true, then it might be a great way to learn about what isn’t in the staff handbook.

May the reverse also be true, what goes on ‘inside’ might also affect what happens ‘outside’? Perhaps our inner-system is the most important system of all, the system that we should pay the most attention to as we start a new role. A new role can bring considerable change, new relationships, new technical and political challenges, new pressures and stress, as well as new expectations. Expectations include those applied by others and the expectations of performance we apply to ourselves. There may even be issues of loss associated with your old role and, of course, there’s what goes on outside work in our personal lives and our communities, both locally and globally. Possibly, the single biggest influence on our behaviour is our own personal history, including our childhood and relationships with our first family. All of these influences will impact how we show up at work and, if left unexamined, we may not get the chance to take responsibility for them and provide the personal leadership necessary to lead others.

Jungian author James Hollis suggests that our psyche has a way of communicating what remains unresolved within us through the production of anxiety. Distinct from fear, anxiety is like a fog, an indefinable worry that we carry around, sometimes for a while. Fear is of something specific, we know we are scared of it and can name it. This knowledge is helpful and allows us to take on what might be stopping us from making progress in life. Anxiety is often less obvious, unconscious and subsequently more problematic. This communication is valuable data for leaders and worthy of consideration as it may help us work out where we are stuck. It is from this awareness we can find the capacity to change ourselves and lead from our inner-system rather than be a slave to unconscious energies. Starting this journey in your first 90 days of a new role might be the thing that most helps you to create the sustainable impact you seek.